Introduction of Music

Since the beginning of time, music has played an essential part in our identities, cultures, and lifestyles. Music can be found almost everywhere, from the stomping of the feet to the chirping of birds. It defines who we are, and how we interact with things.

Music can be grouped by instrument, genre (such as pop, rock, or classical to name a few), key signature, time signature, and even time period (like classical or romantic). But the most simple way of categorizing music is determining if it is major or minor.

Minor and Major

Major music is notes that are audibly pleasing, or happy. Songs like Taylor Swift’s famous “Paper Rings”, or the classic “Jingle Bell” are obvious examples of songs in a major key. Major scales, (the notes played between an octave that has a major connotation) such as the C Major scale, are also examples of major music. When played, the C scale gives a sense of satisfaction and completeness. The same is true for the F Major scale, which contains one flat (half a note down from the primary note) to ensure the F Major scale is truly major. Without the flat, the F Major scale would sound incomplete, and leave any musician in a state of aggravation.

Minor music, on the other hand, is sad and depressing. Songs like Billie Ellish’s “Happier Than Ever”, or “Bohemian Rhapsody” written by Freddie Mercury, are songs in a minor key. Minor scales, (the notes played between an octave that has a minor connotation) after being played, give, like major scales, the sense of completion. But unlike major scales, minor scales sound eerie and mysterious.

What Makes Makes Minor Chords Sound Sad?

Each time a note is played, it creates a wave. This wave is what we identify notes with; if the note G is played, the wave it creates is also a G. But each wave creates faster vibrating waves, which adds to the sound of the note. This means that when a C is played, faster moving waves also create an E, a G, a B♭ , and so on until we cannot hear the additional waves being created.

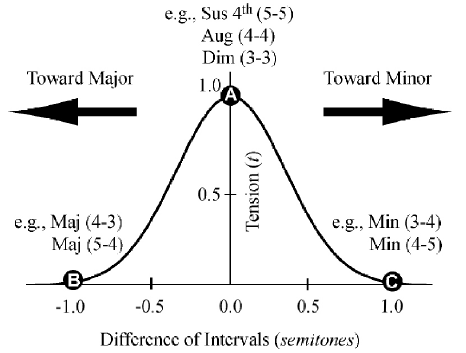

When a two notes, such as F and G are played at the same time, the newly created waves clash with each other, making our ears receive mixed sound waves. Our eardrum sends electrical signals to our brain in a unorganized manner, causing our brain to release random chemicals which make us feel sad. This is called harmonic tension.

Related Articles

https://www.psycho.hes.kyushu-u.ac.jp/~lab_miura/Kansei/Workshop/proceedings/O-205.pdf

https://www.sciencefocus.com/science/why-are-minor-chords-sad-and-major-chords-happy

https://www.nme.com/blogs/nme-blogs/the-science-of-music-why-do-songs-in-a-minor-key-sound-sad-760215

https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/sound/Lesson-4/Fundamental-Frequency-and-Harmonics

https://homepage.ntu.edu.tw/~karchung/phonetics%20II%20page%20eight.htm#:~:text=The%20harmonics%20are%20multiples%20of,880%20Hz%2C%20and%20so%20on.

Take Action

https://alexanderchen.github.io/harmonics/ – Use this website to hear 16 base waves

https://academo.org/demos/wave-interference-beat-frequency/-This site is an interactive program where you can experiment with standing waves