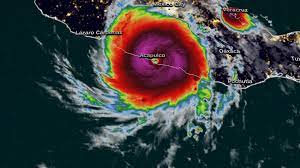

Early Wednesday morning, Hurricane Otis was the strongest storm to hit the Pacific coast of Mexico. The Category 5 hurricane made landfall near Acapulco, where its heavy rains and 165 mph winds triggered massive landslides and brought down power lines, killing at least 20 people and causing widespread destruction.

But just 2 days earlier, meteorologists doubted that Otis—then a tropical storm—would even reach hurricane status. Forecasters at the US National Hurricane Center expected the storm to gradually intensify, with most computer models predicting maximum winds of about 60 mph. Instead, as Otis headed toward the coast of Mexico, its winds increased to 100 mph in 24 hours, a “rapid strengthening” record. For meteorologists, it was a tragic reminder that while forecasting methods have improved greatly in recent years, it is another matter to predict when a small storm will suddenly explode into a catastrophic hurricane.

The two keys are warm ocean and moist air, which together feed the convective forces at the center of the storm. Sharanya Majumdar, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, notes that ocean waters have been “unusually warm” during this year’s hurricane season. As Otis approached the coast, he crossed an area of water with a temperature of 71 Fahrenheit, several degrees warmer than the expected average for late October. For a hurricane to increase in strength, it must be free of crosscutting winds, called wind shear, which can tear holes in the walls of the eye of the storm or throw it off. Earlier in the week, when Otis still resembled a normal tropical storm, some forecasters noted that environmental factors could make it more dangerous, but the structure of the storm did not seem organized enough to take advantage of it. And while the wind shear was weak, Kaplan said it wasn’t exceptionally low.

When thunderstorms that rotate around the center of a hur

ricane are symmetrical, the heat remains concentrated in the eye of the storm instead of being dispersed over a larger area. The symmetry also causes dramatic pressure drops in the center of the storm, which increases wind speed. When that happens, “there’s nothing stopping it from becoming a monster,” says NOAA meteorologist Sundararaman “Gopal” Gopalakrishnan. But thick clouds prevent most satellites from seeing these internal conditions. Based on the available data, computer simulations predicted that Otis would become progressively more efficient. It wasn’t until late Tuesday night, when planes were able to fly through the storm and take direct measurements, that forecasters realized their models had gone wrong.

That delay spelled disaster for the residents of Acapulco, who were largely caught off guard when Otis hit the

Mexican coast. “Our predictions simply didn’t give residents enough time to properly prepare,” says Tang. “If you’re a little behind the ball, it’s too late.” As climate change heats up around the world, some scientists worry that rapidly intensifying hurricanes like Otis will become more frequent. “It’s not easy to make very clear predictions about the future,” Majumdar says, noting that it’s not clear whether such storms are actually becoming more frequent. However, he adds, recent evidence points to an increasing trend and ocean warming as the driving force. If more Otis-like storms are indeed on the horizon, forecasters and their computer simulations must get better at predicting them. “There’s definitely a long way to go,” Kaplan says, noting that the resolution of current models isn’t high enough to analyze smaller storms, which are particularly sensitive to environmental factors and can weaken or intensify at incredible speeds. Gopal, who served as the chief architect of NOAA’s state-of-the-art Hurricane Weather Research and Prediction System, explains that models are only as good as the data that feeds them. Because rapidly intensifying hurricanes have so far been rare, this kind of information is scarce. Ultimately, Kaplan adds, any model or meteorologist has limitations. “Nature is sometimes hard to predict,” he says.

Related Stories:

https://www.foxweather.com/weather-news/acapulco-destroyed-hurricane-otis-survivor

https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/4278020-multiple-dead-missing-hurricane-otis-mexico/

https://weather.com/news/news/2023-10-26-hurricane-otis-tropical-cyclone-acapulco-mexico-updates

https://www.wcvb.com/article/hurricane-otis/45632631

Related Stories: