Women In STEM: Part 2: Technology

One of four women who changed our perception of the world…but never got credit for it.

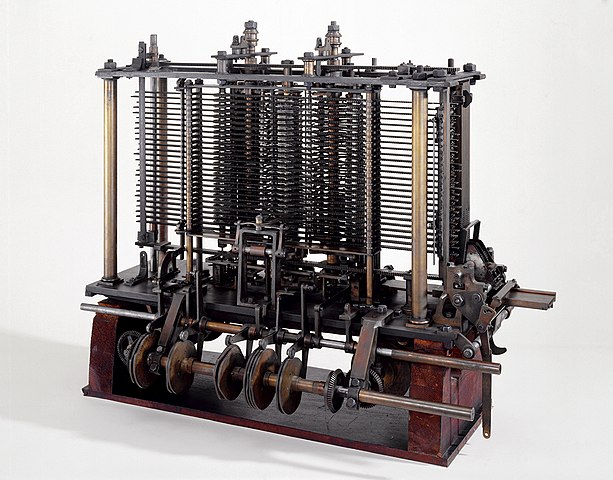

Source: Science Museum

“File:Babbages Analytical Engine, 1834-1871. (9660574685).jpg” by Science Museum London / Science and Society Picture Library is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/?ref=openverse.

Technology:

Unlike Rosalind Franklin, the work of Ada Lovelace wasn’t covered up by men, but simply obscured by history. Most people don’t even recognize her name. But she worked on Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, a proposed mechanical general-purpose computer. Back then, computers weren’t used for playing video games or sending e-mails. The only purpose of them was to do mathematical equations, or compute numbers, which is where the word “computer” comes from. But Ada Lovelace was the first one to realize that the machine had potential beyond simple calculation, and was known as the first computer programmer for the algorithm that she wrote. Here is her story.

Ada Lovelace was born Augusta Byron to Lord and Lady Byron in 1815. Her father expected his only legitimate child to be a “glorious boy”, and was disappointed when she turned out to be a girl. Baby Augusta was called “Ada” by Lord Byron, and the nickname stuck.

But Lovelace did not have any kind of relationship with her father at all, as he and her mother formally separated when she was only a few months old. When she was eight, he died in Greece, and she was not shown a portrait of him until she turned 20.

Lovelace’s mother loved math and believed that it was important for young women to be educated; Ada in particular so that she would not develop her father’s temper, moodiness, and perceived insanity. Her mathematic and logic skills began to emerge at an early age, and she was very clever. The Industrial Revolution was occurring, and there were a lot of fascinating new inventions. Ada Lovelace was amazed by all of these machines, and she loved to dream up her own, including a “flying machine” that she designed when she was only twelve.

She was taught by several different tutors, including the family doctor. When Lovelace was 18, the inventor Charles Babbage, through a mutual friend, met her and was enchanted by her intellect. He had a few nicknames for her, including “Enchantress of Number” and “Lady Fairy” (a nod to her petite size). Babbage arranged for Lovelace to study advanced mathematics at the University of London, unusual for a young lady of that day.

In 1835, she met and married William King, who was to become the Earl of Lovelace in 1838, making Ada King into Ada Lovelace. They had three children: Byron, Anna Isabella, and Gordon. The names of her two sons show an interest in her estranged father, despite her mother’s bitter attempts to cut him out of their life. King supported his wife’s studies, and the couple were friends with many influential people living in London, including the famous author Charles Dickens.

Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage continued to meet, so fascinated were they by each other’s skills and inventions. At the time, Babbage was famous for his “Difference Engine”, which was the world’s first number-computing machine. But he had plans for another, better computer: the Analytical Engine. Supposedly, it could perform even more complex mathematical calculations. An Italian mathematician named Luigi Menabrea wrote an article about the engine, and Lovelace was asked to translate it from French into English. She cleverly added her own notes and studies to supplement the article, making it four times as long as it was before.

Lovelace’s ideas shook up society, particularly her theories about how symbols and letters could be turned into codes that the Analytical Engine could handle along with numbers. She thought about how the computer might be able to take one sequence of operations and repeat it over and over. Today, this is called “looping”, and it is one of the fundamental parts of modern devices. One thing she got wrong, however, was her perception of AI, artificial intelligence. She believed that it was impossible for a piece of machinery to make its own decisions, and it could only do things that its programmer told it to do. Modern scientists have proven that this was one of the rare instances where her ideas were wrong.

Ada Lovelace died of cancer, poor and alone, and she did not live to see all of her ideas come full circle. In the 1940s, a computer scientist named Alan Turing was one of the first ones to truly recognize her pure genius.

RELATED STORIES:

Halligan, Katherine. HerStory: 50 Women and Girls Who Shook Up the World. Great Britain, Nosy Crow Ltd., 2018.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ada-Lovelace

https://www.computerhistory.org/babbage/adalovelace/

https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/ada-lovelace-the-first-tech-visionary