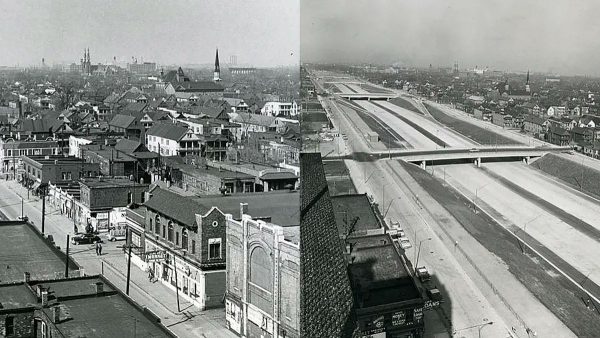

A American urban planning has long been defined by its car-centricity, its prioritization of the automobile over the pedestrian, and its sprawl. But this wasn’t always the case. Before our cities were defined by urban freeways and single-family suburbs, our cities catered to the needs of the pedestrian, not the car. On a city street, you could find a mix of streetcars, bicycles, and pedestrians, which didn’t fit in with the form of transport that is the car.

With the advent of the automobile, cars and car-centric planning gradually took over streetscape design in the United States. And with the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act and the new wave of urban renewal in the 1960s spearheaded by eccentric urban planner Robert Moses, city governments finally had an excuse to destroy minority neighborhoods in the name of removing “urban blight.” With the federal government picking up 90% of the cost, freeway construction made it easier for politicians and business leaders to pursue their own “urban renewal” projects, prioritizing suburban commuters at the expense of thriving neighborhoods.

These new highways separated and destroyed many neighborhoods, lowering property prices and often leading to the destruction of these neighborhoods.

“Many neighborhoods, predominantly black, were wiped out and turned into surface parking and highways,” says Peter Norton, a historian at the University of Virginia.

The people displaced from the destruction of their neighborhoods had two choices: move into other neighborhoods, leading to overcrowding and increased crime, or, if you had the means, move to the suburbs, using the new highways and destroying the cities’ tax bases.

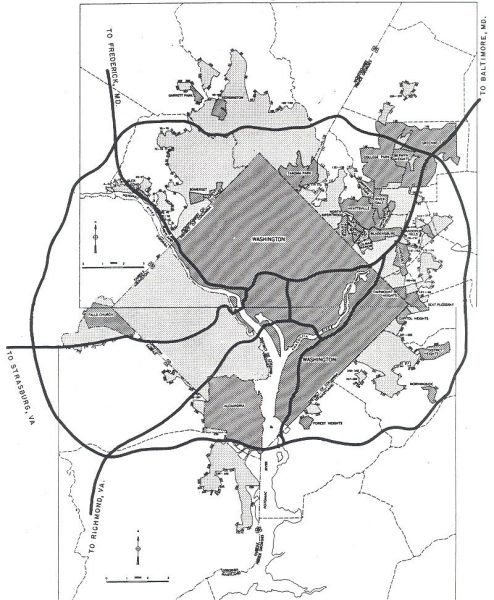

But this wasn’t the case for many well-off neighborhoods. City governments and wealthy residents were often able to stop the construction of highways through their homes. For example, Wisconsin Avenue in DC was planned to become a highway, but it never came to fruition due to protests by the area’s wealthy residents.

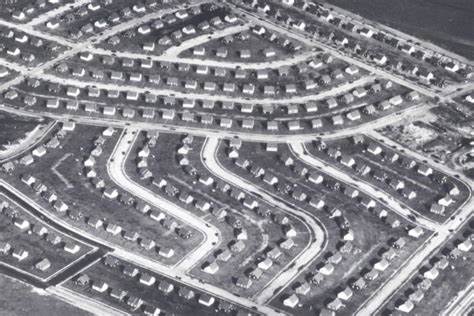

“White flight” and the rise of suburbs

These new highways subsidized suburban development and enabled “white flight” from cities, as suburbs were often restricted to white buyers only, either through the discretion of the property developer or regulations limiting mortgage loans to black or minority home buyers, which often made them have to pay more for a home in the long run compared to a white homeowner. Throughout the 1950s through the 1970s, the suburban population reached a peak of 74 million. Cities, left deserted and decimated, found themselves with lowered populations and rising crime rates. American families who owned cars increased from 54 percent in 1948 to 74 percent in 1959, and by 2016, 95 percent of Americans owned cars.

The future

Mixed-use zoning reforms, investments in public transit, and redundant highway removal are all solutions being implemented to address the consequences of the highways that have divided American cities for years. President Joe Biden’s trillion-dollar Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has set aside $66 billion for passenger and freight rail, and the Inflation Reduction Act has set aside $3 billion to fund highway removal. As we look to the future, it’s clear that reimagining our cities involves more than just tearing down highways; it involves a comprehensive development plan that prevents the mistakes that caused the urban problems we face today.

RELATED STORIES:

https://www.ft.com/content/27169841-7ee3-481e-919d-41b247e401f6

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/27/climate/us-cities-highway-removal.html

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/07/984784455/a-brief-history-of-how-racism-shaped-interstate-highways

https://www.c-span.org/video/?317148-1/rise-automobiles-american-city-planning

TAKE ACTION:

I-375 Reconnecting Communities Project | City of Detroit (detroitmi.gov)