As wearable sensors become smaller and more accurate, designers and engineers can re-imagine medical monitoring as everyday objects, for example, a heart-rate monitor built into a necklace. Devices like this can monitor health regularly while also serving as personal decoration. When thoughtfully designed, they can reduce barriers to use, preserve dignity, and support independence for children, older adults, and people with disabilities. However, use depends not only on technical performance but also on comfort, privacy, aesthetics, and social meaning.

How and why does wearing medical devices affect people?

Wearing a medical device can affect people physically (skin irritation, fit, comfort), psychologically (anxiety and identity shifts), and socially (visibility and perceived shame). Research on older adults shows that continued use of wearables depends on motivation, the device’s recognized usefulness, easier ways of using medical devices in daily lives, and social and support structures around the user. Simply having accurate sensors is not enough for long-term adoption. In addition, studies on medical aesthetics and shame show wearable health devices can cause embarrassment or identity concerns when they look “medical” rather than like regular clothing or jewelry, which can reduce use even when clinical need exists. Designers must address modesty and the social meanings a device projects.

How can jewelry design promote independence and dignity?

Turning a monitor into a piece of jewelry changes how it is perceived and used. Framing a device as an attractive accessory with customization options, familiar materials, and user input to their personal design increases the device’s high and aesthetic value, which studies show raises the likelihood that older adults will adopt and keep using it. The World Health Organization stresses that assistive products that support functioning and independence that are co-designed with users to improve inclusion and quality of life, aesthetic, non form factors are part of making assistive technologies acceptable and accessible to more people. For caregivers and clinicians, a discreet, jewelry-style monitor can lessen visible dependence while still giving family and providers timely data — supporting independence without isolating the user.

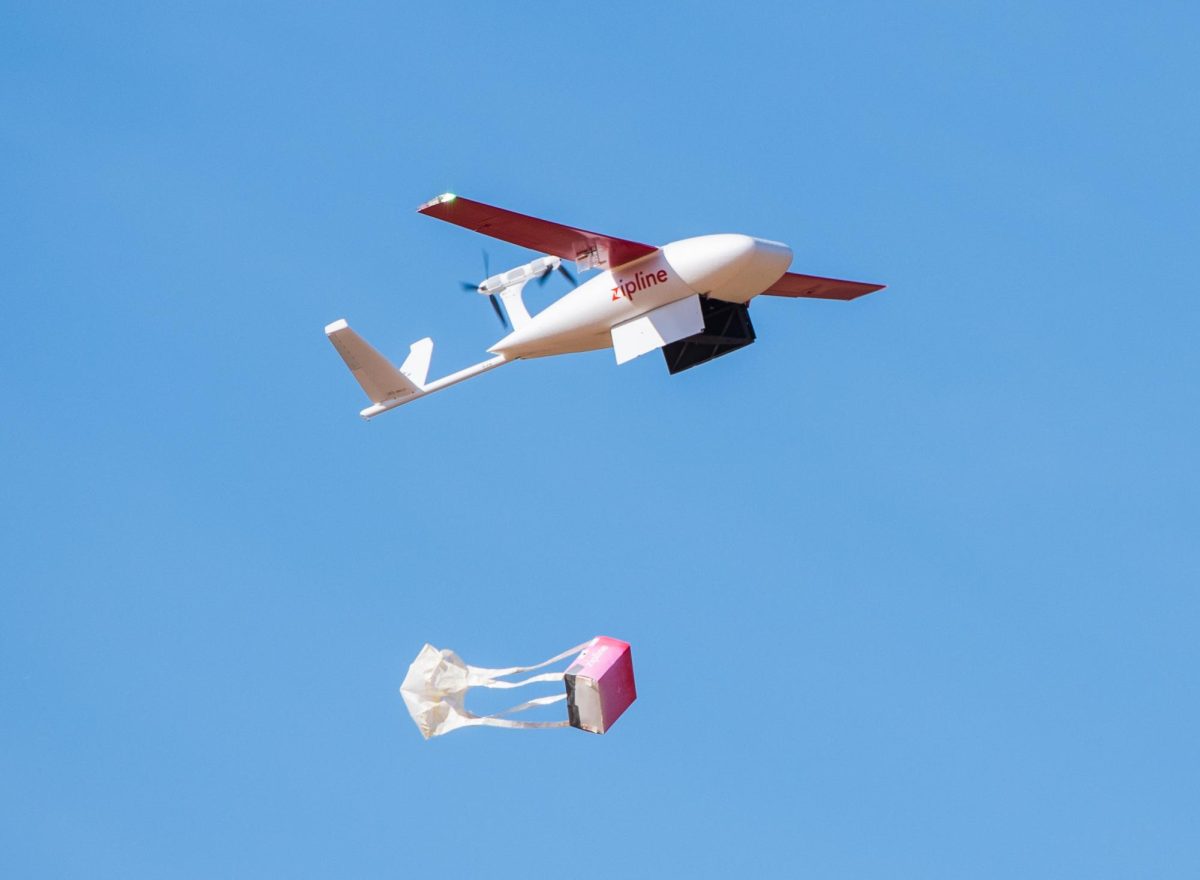

How can personalized wearable technology change healthcare?

Personalized wearables devices tailored to an individual’s body, preferences, and clinical signals are positioned to decentralize monitoring, enable earlier intervention, and make long-term health data part of daily life rather than only clinic visits. Reviews and commentaries in digital-medicine and biomedical engineering literature describe a shift toward continuous, remote, and personalized monitoring that can improve preventive care and equity if privacy, data quality, and accessibility are addressed. When necklace monitors reliably capture heart rate and connect securely to caregivers or electronic records, clinicians can detect trends, intervene sooner, and support self-management — but success requires attention to data security, integration with care pathways, and inclusive design so benefits reach diverse users.

A heart-rate necklace for children, older adults, and people with disabilities is more than a sensor plus band; it is a design challenge that blends engineering accuracy with human factors, aesthetics, and ethics. Devices that prioritize comfort, appearance, privacy, and co-design increase adoption and support independence. If developers pair personalized, unobtrusive hardware with secure data practices and clinical integration, wearable jewelry could shift healthcare toward continuous, equitable, and person-centered monitoring — giving users better control over their health without sacrificing dignity.

Works Cited

Kang, H., & Exworthy, M. (2022). Wearing the future — Wearables to empower users to take greater responsibility for their health and care: Scoping review. https://doi.org/10.2196/35684

Moore, K., et al. (2021). Older adults’ experiences with using wearable devices: Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8212622/

Wall, C., Hetherington, V., & Godfrey, A. (2023). Beyond the clinic: The rise of wearables and smartphones in decentralising healthcare. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00971-z.

Walter, J., Xu, S., & Rogers, J. (2024). From lab to life: How wearable devices can improve health equity. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44634-9.

World Health Organization. (2024, January 2). Assistive technology. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology.